Ahead of the first ever nitrogen execution, next week, it’s worth revisiting what we know about the lead executioner, who will oversee this experiment. He was fired from state police after he assaulted women and owed money to people with criminal records.

A former Alabama State Trooper fired two decades ago and who a judge would later describe as a man who “beats on women, consorts with felons, and neglects his official duties,” is now the state executioner and warden at one of the state’s most notorious prisons.

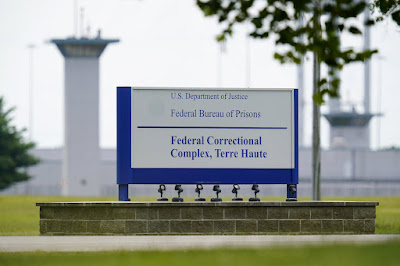

Terry Raybon became the warden of William C. Holman Correctional Facility in Atmore in 2021. Holman is where the majority of death row inmates in the state are housed, and it’s the only facility in the state to perform executions. There are currently 165 inmates on Alabama’s Death Row. [This article was published in August 2022.]

Alabama state law declares Holman’s warden as the state executioner.

But before Raybon became the leader of Holman and the state executioner, he was fired from his position as a state trooper. The incidents leading to his termination were detailed in an April 2000 federal lawsuit he filed, claiming the Alabama Department of Public Safety’s and its supervisors’ decision to fire him was racially motivated.

A judge ruled in April 2001 that Raybon’s firing was not racially motivated and issued a scathing report.

“The Alabama Department of Public Safety fired a state trooper who beat up two of his female acquaintances, refused to perform his work acceptably, and incurred various debts from convicted felons. That should have been the end of it, since in any sane world the police should not be required to employ persons of questionable character,” District Judge Ira De Ment wrote.

“But this state trooper has made a federal case of it, alleging that he was canned because of his race.”

Lawsuit

Raybon started working for the troopers in December 1985, according to the lawsuit. In November 1998, an acting chief of the department recommended Raybon be suspended without pay.

According to a state filing in the lawsuit, the chief cited three reasons why:

The first was a “domestic violence altercation” in Troy in October 1998. According to a state filing, a report was made which indicated Raybon “beat or used physical force against a woman to such extent that hospital treatment was necessary.” De Ment’s 2001 order ruling against Raybon said a doctor diagnosed the woman with a perforated left ear drum and multiple bruises, and that Raybon denied hitting her. It states the woman was from Australia and traveled to Alabama to meet Raybon after she met him online, where he used the name “Supertrooper.” The judge added that the woman went back home after the incident “defeated and with a broken spirit.”

The second was that Raybon was in debt and he refused to pay.

And the third reason, according to a suspension letter, was that Raybon showed “a series of lack of attention to (his) assigned duties and failure to submit reports.” It indicated Raybon didn’t submit driver’s license and vehicle inspection reports, arrest reports, or incident reports.

According to court records and records in his state personnel file, Raybon did not appeal this suspension and accepted the 30-day suspension without pay.

The chief gave Raybon a warning, which was detailed in the state’s court filings. It said in part: “In short, there is no one except yourself that can cure your problems.”

It also stated that if there was “ever again even the slightest indication” of a policy violation, Raybon would be fired.

Raybon was suspended from Dec. 19, 1998 until Jan. 17, 1999.

Less than 30 days after returning to work, Raybon was again involved in a domestic violence altercation in Prattville, according to the state’s filing.

The report, noted in the lawsuit, stated that on Feb. 19, 1999, Raybon “used physical force against a woman in a hotel room, causing injury to her by striking her face with a telephone, pushing her and breaking off a fingernail.” According to the judge’s order, “Raybon had developed a romantic relationship with the woman, and it turned out that Raybon now owed her several thousand dollars.”

An investigation later revealed she was a convicted felon. DPS policy forbids troopers to have “open or frequent association” with convicted felons who are not family members.

A filing from Raybon’s lawyer said Raybon didn’t know that the woman was a convicted felon and that he didn’t intend to hit her when he “tossed” the telephone to her.

The same chief recommended Raybon be fired and along with an administrative review board, and he was terminated from the position in March 1999.

“...the department has determined that you are a danger to the public and our attempt to help you rehabilitate yourself has failed,” the acting chief of the highway patrol division wrote.

Raybon appealed to the state personnel board where records show an administrative judge upheld the firing. Raybon also made an Equal Employment Opportunity Commission complaint, but the EEOC was unable to conclude any violation occurred, records in the lawsuit state.

Ruling

The judge added in his order, “no rational jury could conclude that race motivated the Department’s actions.” The order also calls one of the domestic violence accusations against Raybon a case of him beating “a woman mercilessly.”

De Ment wrote that Raybon presented no evidence that white employees were treated differently, and that none faced “repeated acts of domestic violence.”

A brief from Raybon’s legal team details other unidentified troopers who received small or no punishments for other incidents, but only one trooper mentioned was facing a domestic violence accusation. In that case, a white female trooper was arrested for domestic violence after an altercation with her husband, who was a retired trooper. The department-- including the same supervisors who punished Raybon-- took no disciplinary actions against the female trooper, according to the lawsuit.

The brief does not mention any other details about that incident, nor name either party involved.

De Ment said in his order, “A state trooper who beats on women, consorts with felons, and neglects his official duties is a menace to the public who, of course, may be lawfully terminated.”

He added: “A law enforcement agent who tussles and brawls at a local hotel forfeits any freedom from a subsequent inquiry into his fitness to serve as a monopolist on the state’s use of deadly force.”

ADOC

Raybon started working at the Alabama Department of Corrections in 2000, about one year after being fired from the state trooper’s office.

According to his state personnel file, he worked at Wal-Mart as a loss prevention officer between his firing at DPS and his hiring at the ADOC.

In that file, a letter dated September 20, 2000, from the ADOC personnel division showed Raybon applied for a job with the ADOC but was not recommended for the position by DPS. “Before we can consider you for employment you must be recommended for reemployment by the Department of Public Safety,” the letter states.

The file, provided to AL.com by the state personnel office, jumps from that document to an ADOC work evaluation form covering the dates between November 2000 and May 2001. There is no documentation on when Raybon was hired at the ADOC, or if DPS ever submitted a recommendation.

Records show Raybon was promoted several times throughout his ADOC career: In 2004, when he was promoted to Correctional Officer II; in 2009, when he was promoted to Correctional Lieutenant; in 2011, when he was promoted to Correctional Captain; in 2013, when he was promoted to Correctional Warden I; in 2014, when he was promoted to Correctional Warden II; and in 2020, when he was promoted to Correctional Warden III. Raybon is still listed as Correctional Warden III on the ADOC website.

His time at the ADOC has not been without incident. Raybon’s personnel file details a five-day suspension in June 2009 for an incident in January of that year. A document from the commissioner, included in the personnel file, states Raybon “initiated and engaged in a physical altercation” with an officer at St. Clair Correctional Facility.

In that incident, the record states Raybon pushed an officer with his fist, approached the officer aggressively, grabbed the officer and pushed him into a brick wall.

That report is followed in the personnel file by a document dated July 6, 2009, announcing Raybon’s promotion.

GTMO

In the early days of the war on terror, Raybon served at the U.S. prison camp in Guantanamo Bay in Cuba. Copies of Raybon’s resume included in his personnel file show he is a decorated Army veteran who served as a Plans/Operation Officer on Active Duty from 2002 to 2004. During that time, he worked “as one of the lead planners for the (GTMO) detainee mission in Cuba.”

GTMO is the United States military base located at Guantanamo Bay and includes a military prison where many of those captured in the war on terror have been housed.

He also received a Department of Defense Global War on Terrorism Medal in 2004.

Raybon declined a request for comment, according to the Public Information Officer at ADOC.

Source:

al.com, Ivana Hrynkiw, August 18, 2022

_____________________________________________________________________

.jpg)