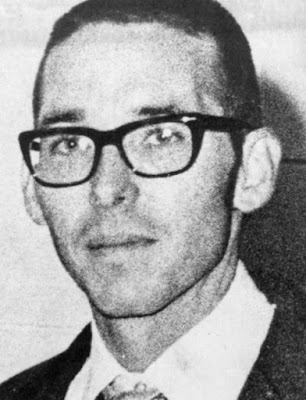

Tommy Zeigler has been on death row since 1976. The state has rejected his repeated requests for DNA testing.

The state attorney’s office that prosecuted Tommy Zeigler for the murders of his wife, in-laws and another man at his furniture store on Christmas Eve 1975 says that it is taking a fresh look at his case.

And a Florida state representative says he wants to introduce legislation to address both prosecutorial misconduct and problems with access to forensic science, including DNA testing.

Zeigler, who has been on death row for 42 years, was recently the subject of a multi-part investigation in the Tampa Bay Times. He has asked six times for advanced DNA tests of clothing, fingernail scrapings and guns still in evidence at a climate-controlled locker in Orlando. The 73-year-old’s lawyers have agreed to pay for the testing.

For about 2 decades, the Ninth Judicial Circuit state attorney’s office has rejected Zeigler’s requests. But State Attorney Aramis D. Ayala’s office now includes a conviction integrity unit, established in September. And the director of that unit is looking over the Zeigler case, according to a spokesperson for Ayala’s office. The office’s policy states that it will only “review applications where a plausible claim of innocence exists.” Ayala herself has declined to be interviewed.

“That’s a big deal,” said Zeigler’s original attorney, Terry Hadley, who wrote to Ayala last month, encouraging her to review the case. “It means that we at least got her attention, if nothing else.”

Rep. James Grant, an attorney and a Republican from Tampa representing northern portions of Pinellas and Hillsborough counties, said he wants to address the issues that have made Florida the state with the most exonerations from death row with reforms.

“If a defendant wants to bear the costs to test evidence as science continues to advance but can’t access the evidence to test it, I find that troubling,” he said.

Grant, recently named chairman of Florida’s House subcommittee on criminal justice, would like to see changes included in the reform package likely to emerge in the legislative session that convenes in March.

“If we take someone’s liberty, let alone their life, it’s pretty darn important that we get it right,” Grant said.

He said he would like to see a process for inmates, particularly those convicted with junk science, to use DNA and other reliable tests. But there would have to be a mechanism to prevent senseless appeals. And he’d like to see consequences for those who willfully withhold or destroy evidence, something that rarely happens now.

Zeigler is one of almost 2-dozen men sent to death row in the 1970s and 1980s who can’t get advanced DNA testing of evidence, even though Florida passed a DNA testing statute almost 2 decades ago.

A Times review of 46 men on death row who asked for permission to conduct DNA testing found that judges turned down 38 of them at least once. Nineteen men were denied all DNA testing, including eight who were later executed.

Another 17 death row inmates, including Zeigler, were allowed tests initially but then denied more advanced testing, including touch DNA.

Nearly 70 % of those denied at least 1 test were convicted before DNA testing existed. Many of the cases are, like Zeigler’s, based on circumstantial evidence and witness accounts.

9 of the men were found guilty with the help of microscopic hair comparison, which has since been discredited. Another 4, including Zeigler, were convicted with the help of blood spatter analysis, a method criticized as more speculation than science.

In 2001, Zeigler got permission during a clemency appeal to test the blood on his shirt and the pants of one of the dead, Charlie Mays. A forensic scientist selected 4 locations for testing, which he said would identify whether Zeigler was the killer. Zeigler and his attorneys have always maintained that Mays was there with several others to rob the store that Christmas Eve.

The DNA analysis on Zeigler’s shirt did not reveal blood from his father-in-law, Perry Edwards Sr., who had been shot at close range and bludgeoned with a metal crank. Mays’ pants, however, did have Edwards’ blood.

Prosecutors said Edwards’ blood could be elsewhere on Zeigler’s shirt, but they wouldn’t allow further testing.

Hadley, who defended Zeigler in 1976, said DNA testing would either “set him free or it could affirm the crazy narrative of the prosecution.”

“For the prosecutor’s timeline to work,” he said, “a man with no criminal record had to blow away 4 people on Christmas Eve and try to frame a group of black men on the same night that the police chief was supposed to pick him up for a party.”

Denials in Zeigler’s case have been used to prevent other men on death row from getting DNA testing. Quite often, judges say the original evidence pointing to the convicted person is too strong to overcome.

But experts say exonerations around the country have demonstrated how much police and prosecutors got things wrong.

“The lesson from DNA cases is not that DNA has the possibility of establishing that someone else did it,” said Robert Dunham, executive director of the Death Penalty Information Center in Washington D.C. “It’s that the DNA proves that all the other evidence in the case was wrong.”

Clemente Aguirre-Jarquin, convicted and sentenced to death for fatally stabbing two of his Altamonte Springs neighbors in 2004, is an example. The undocumented Honduran immigrant, then 24, was found with the victims’ blood on his clothes. He said he touched the knife because he feared the killer might still be present and checked the victims for signs of life. DNA tests in eight locations later uncovered the blood of a woman who had confessed to the murders. After 14 years in prison, Aquirre-Jarquin was finally released late last year.

And the Florida Supreme Court overturned the conviction of Paul Hildwin in 2014 after DNA testing showed he did not rape the victim, as prosecutors said at the trial. Hildwin, who spent 32 years on death row, has been waiting four years in the Hernando County jail for a new trial.

Henry Sireci, 70, has, like Zeigler, spent 42 years on death row. He was sentenced to death for killing a used car lot owner on Dec. 3, 1975 in Orange County, about three weeks before the murders at the Zeigler furniture store.

A crime lab analyst compared a hair found on the victim’s sock with a hair from Sireci and said it was a match, “in all probability.” But a Justice Department review has since found many hair comparison examiners made claims that exceeded the limits of science. In 2013, the FBI and American Society of Crime Laboratory Directors acknowledged that previous hair comparison analysis was invalid.

But the courts concluded there was enough other evidence against Sireci, so he was not allowed to conduct a DNA test of the hair. Sireci had confessed to the crime multiple times, though his lawyers say he has brain damage and is “functionally retarded.”

In 2016, Sireci’s attorneys asked the U.S. Supreme Court whether his federal rights had been violated when the trial court refused to grant him a new trial or the DNA test. The Supreme Court refused to hear the case.

Justice Stephen Breyer dissented, arguing that keeping men on death row for decades essentially amounted to cruel and unusual punishment. (In fact, 10 men have spent more than 40 years on Florida’s death row, including Sireci and Zeigler.)

Breyer complained that some of those executed are not the “ ‘worst of the worst’ but rather, are individuals chosen at random on the basis, perhaps of geography, perhaps of the views of the individual prosecutors, or still worse on the basis of race.”

Florida has a history of convictions tainted by racism, official misconduct and questionable judgments.

For every Ted Bundy and Aileen Wuornos executed in Florida, there was a Willie Darden and Beauford White and David Livingston Funchess.

Darden, a black man once known as the Dean of Death Row, was convicted in 1973 by an all-white jury of killing a white Lakeland furniture store owner. Prosecutors purposefully kept blacks off the jury, a practice later declared unconstitutional. White did not shoot anyone and tried to talk his fellow robbers out of killing 6 people in a Miami suburb. The jury gave him life. But a judge overruled the jury, and he was executed -- 26 years before 1 of the men who pulled the trigger. Funchess, a Vietnam vet and Purple Heart recipient with post-traumatic stress disorder, was executed in 1986 for stabbing 2 employees at a bar in Jacksonville.

Today, every state has a DNA testing law, but inmates across the country struggle for access.

In December, California Gov. Jerry Brown ordered DNA tests to be conducted in the 35-year-old case of a man accused in a quadruple murder after prodding from New York Times’ columnist Nicholas Kristof, U.S. Sen. Kamala Harris and Kim Kardashian.

Several death penalty experts and Florida attorneys working on appeals for death row inmates said judges are tired of frivolous appeals. They have large dockets and are unwilling to allow “fishing expeditions.”

“It’s a battle between finality and the truth,” said Michelle Feldman, legislative strategist for the Innocence Project in New York City. “I understand that you don’t want procedures to go on forever, but truth is more important.”

Source: Tampa Bay Times, Leonora LaPeter Anton, January 3, 2019

⚑ | Report an error, an omission, a typo; suggest a story or a new angle to an existing story; submit a piece, a comment; recommend a resource; contact the webmaster, contact us:

deathpenaltynews@gmail.com.

Opposed to Capital Punishment? Help us keep this blog up and running! DONATE!

"One is absolutely sickened, not by the crimes that the wicked have committed,

but by the punishments that the good have inflicted." -- Oscar Wilde