A half-century after Justice Lewis Powell applied the logic of tobacco manufacturers to dismiss empirical studies, a state supreme court decided to accept their findings.

Last week, the American death penalty lurched on step closer to its eventual demise, as the Washington Supreme Court decided to fan away some of the smoke from Lewis Powell’s cigarette.

In

State v. Gregory, the state court held that the death penalty, as imposed in the state of Washington, was unconstitutional because it was racially biased.

How does that relate to Powell and tobacco? Fastidious and health conscious (acquaintances remember seeing him order a turkey sandwich for lunch, then set aside the bread and eat only the turkey), Powell was a non-smoker. But he also sat from 1963 until 1970 on the board of Virginia-based tobacco giant Philip Morris. Like all members of the board, he posed in the customary annual photo with a lit cigarette in his fingers.

Over the past half century, that cigarette has befouled the U.S. Supreme Court’s miserable handing of capital punishment. In 1972, the Court put a moratorium on death sentences. It held that Georgia’s capital punishment laws violated the Eighth Amendment’s ban on “cruel and unusual punishment.” The justices could not agree on a rationale—but the case came to stand for the idea that the death penalty by itself might not be unconstitutional, but would be so if state systems were arbitrary or racially biased. The result was a 15-year scramble by state legislatures to design a more consistent way of choosing which murderers to put to death.

That revised system was tested in a 1987 case called

McCleskey v. Kemp.The defendant, Warren McCleskey, was an African American man sentenced under Georgia’s new procedures to die for murdering Atlanta police officer Frank Schlatt. McCleskey challenged his sentence by proffering a massive statistical study of the death penalty in Georgia by legal scholars David Baldus and Charles Pulaski and statistician George Woodworth. They concluded that, controlling for other variables, murderers who killed white people were four times more likely to receive a death sentence than those who killed African Americans. In other words, it said, Georgia was “operating a dual system,” based on race: the legal penalty for killing whites was significantly greater than for killing blacks.

Punishing by race seemed a clear violation of the Eighth Amendment’s ban on “cruel and unusual punishment” and of the Fourteenth Amendment’s guarantee of “the equal protection of the laws.”

But the Supreme Court divided. Four justices—Justices William Brennan, Thurgood Marshall, Harry A. Blackmun, and John Paul Stevens—voted to reject Georgia’s racist system. Four others—Chief Justice William H. Rehnquist and Justices Byron White, Sandra Day O’Connor, and Antonin Scalia—wanted to approve it.

Powell cast the deciding vote and wrote the majority opinion, concluding, “At most, the Baldus study indicates a discrepancy that appears to correlate with race. Apparent disparities in sentencing are an inevitable part of our criminal justice system.”

Statistical evidence, Powell argued, could provide “only a likelihood that a particular factor entered into some decisions”; it could never establish certainty that it had done so in any individual case.

Anyone from the tobacco South recognizes the logic. In 1964, during Powell’s service on the Philip Morris board, the U.S. surgeon general released the famous report, Smoking and Health. Then as now, the numbers were unmistakable: cigarettes kill smokers.

But Philip Morris, like all the rest of the industry, responded with denial. The statistical correlation, the industry said, didn’t prove anything. Something else might be causing the cancer. In response, a member of the company’s board stated, “We don’t accept the idea that there are harmful agents in tobacco.”

The logic Powell applied to the death penalty is the same logic Philip Morris employed while he served on its board. Numbers on paper don’t prove a thing.

The death-penalty lawyer Anthony Amsterdam has called McCleskey “the Dred Scott decision of our time”—the moral equivalent of the 1857 opinion denying black Americans any chance of citizenship. After his retirement, Powell told his biographer that he would change his vote in McCleskey if he could.

But it was too late. The Supreme Court was committed to cigarette-maker logic.

Last week, the Washington Supreme Court, in a fairly pointed opinion, declared that, at least in its jurisdiction, numbers have real meaning. And to those who have eyes to see, numbers make clear the truth about death-sentencing: It is arbitrary and racist in its application.

The court’s decision was based on two studies commissioned by lawyers defending Allen Gregory, who was convicted of rape and murder in Tacoma, Washington, in 2001 and sentenced to death by a jury there. The court appointed a special commissioner to evaluate the reports, hear the state’s response, and file a detailed evaluation. The evidence, the court said, showed that Washington counties with larger black populations had higher rates of death sentences—and that in Washington, “black defendants were four and a half times more likely to be sentenced to death than similarly situated white defendants.” Thus, the state court concluded, “Washington’s death penalty is administered in an arbitrary and racially biased manner”—and violated the Washington State Constitution’s prohibition on “cruel punishment.”

The court’s opinion is painstaking—almost sarcastic—on one point: “Let there be no doubt—we adhere to our duty to resolve constitutional questions under our own [state] constitution, and accordingly, we resolve this case on adequate and independent state constitutional principles.” “Adequate and independent” are magic words in U.S. constitutional law; they mean that the state court’s opinion is not based on the U.S. Constitution, and its rule will not change if the nine justices in Washington change their view of the federal Eighth Amendment. Whatever the federal constitutionality of the death penalty, Washington state is now out of its misery.

Last spring, a conservative federal judge, Jeffrey Sutton of the Sixth Circuit, published

51 Imperfect Solutions: States and the Making of American Constitutional Law, a book urging lawyers and judges to focus less on federal constitutional doctrine and look instead to state constitutions for help with legal puzzles. That’s an idea that originated in the Northwest half-a-century ago, with the jurisprudence of former Oregon Supreme Court Justice Hans Linde. It was a good idea then and it’s a good idea now. State courts can never overrule federal decisions protecting federal constitutional rights; they can, however, interpret their own state constitutions to give more protection than does the federal Constitution. There’s something bracing about this kind of judicial declaration of independence, when it is done properly.

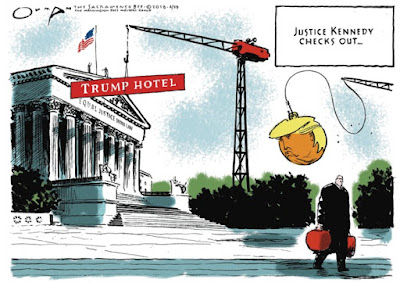

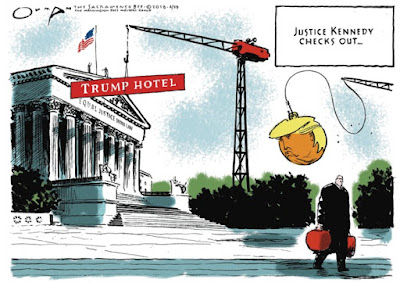

And the Washington court’s decision is well timed. It is immune to the dark clouds gathering over President Trump’s new model Supreme Court. Viewed with the logic of history, capital punishment is on the sunset side of the mountain; but conservative Justices Neil Gorsuch and Brett Kavanaugh are likely to join the other conservatives in lashing the court even more firmly to the decaying framework of official death, no matter how much tobacco-company logic they must deploy as a disguise for its arbitrariness and cruelty.

Smoke may cloud the law in D.C. for years yet. But in the state of Washington, numbers are actual numbers. When racism and cruelty billow across the sky, that state’s courts will no longer pretend they cannot see.

Source: theatlantic.com, Garrett Epps, October 14, 2018. Garrett Epps is Professor of constitutional law at the University of Baltimore.

⚑ | Report an error, an omission, a typo; suggest a story or a new angle to an existing story; submit a piece, a comment; recommend a resource; contact the webmaster, contact us:

deathpenaltynews@gmail.com.

Opposed to Capital Punishment? Help us keep this blog up and running! DONATE!

"One is absolutely sickened, not by the crimes that the wicked have committed,

but by the punishments that the good have inflicted." -- Oscar Wilde