|

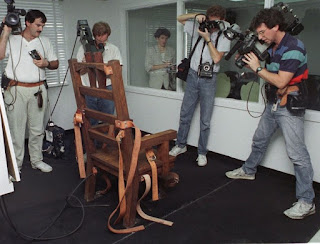

| Florida's death chamber |

A U.S. Supreme Court decision striking down Florida's death-penalty sentencing structure is a "tectonic shift" that should be applied retroactively to all inmates on death row, lawyers for a convicted murderer scheduled to be executed in February wrote in court documents filed Friday.

Lawyers for Cary Michael Lambrix, who has been on death row for more than three decades, have asked the Florida Supreme Court to halt his execution and allow a lower court to sort out whether the U.S. Supreme Court decision, in a case known as Hurst v. Florida, applies to Lambrix.

In an 8-1 decision this month, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that Florida's method of using juries to recommend death sentences, but giving judges the power to impose the sentences, is an unconstitutional violation of the Sixth Amendment right to a trial by jury.

The decision focused on what are known as "aggravating" circumstances that must be found before defendants can be sentenced to death. A 2002 U.S. Supreme Court ruling, in a case known as Ring v. Arizona, requires that determination of such aggravating circumstances be made by juries, not judges.

The Jan. 12 ruling has "far-reaching effects on capital litigation in Florida," requiring more time to digest than is available under the current "expedited" court schedule prompted by the pending death warrant, signed by Gov. Rick Scott in November, Lambrix's lawyers argued Friday in a 106-page brief.

"Each passing day brings new understanding of what Hurst means and implies for capital proceedings in Florida - past, present and future. ... A full airing and judicious consideration of Hurst and its implications cannot and should not be under the exigencies of a death warrant," the lawyers wrote.

Attorney General Pam Bondi's lawyers argued earlier this week that the Hurst ruling should not affect Lambrix's case because his sentence came before the 2002 decision in Ring v. Arizona.

Following the Hurst ruling, the state Supreme Court gave Lambrix's lawyers an extra 2 days - until Friday - to file a brief explaining its impact on his case and whether it applies retroactively to inmates already on death row.

The Florida Supreme Court has typically given inmates condemned to death a year to interpret death penalty decisions issued by the U.S. Supreme Court, Lambrix's lawyers objected, reiterating their request that state justices postpone his execution, scheduled for Feb. 11.

"Hurst requires a global paradigm shift in our understanding of the Sixth Amendment aspects of Florida's death penalty scheme. Hurst establishes that our most basic assumptions about the constitutional integrity of Florida's scheme were wrong. It necessarily opens up new approaches to understanding what is, and is not, unconstitutional in what remains of that scheme," the lawyers wrote.

Lambrix was convicted of killing Aleisha Bryant and Clarence Moore in Glades County in 1983. He met the couple at a LaBelle bar and invited the pair to his mobile home for a spaghetti dinner, documents say.

Lambrix went outside with Bryant and Moore individually, then returned to finish dinner with his girlfriend. Bryant's and Moore's bodies were found buried near Lambrix's mobile home.

Lambrix was originally scheduled to be executed in 1988, but the Florida Supreme Court issued a stay. A federal judge lifted the stay in 1992.

Lambrix has argued that his previous lawyers were ineffective, that he suffers from post-traumatic stress disorder and that the trial court erred in denying DNA tests for a tire iron, Bryant's clothing and a shirt wrapped around the tire iron. Lambrix contends that Moore sexually assaulted Bryant and killed her and that Lambrix killed Moore in self-defense.

A jury recommended that Lambrix be sentenced to death, and a judge imposed the death sentence under the process that the U.S. Supreme Court ruled was unconstitutional, Lambrix's lawyers wrote.

The Florida Supreme Court should apply Hurst retroactively, as it did after a U.S. Supreme Court ruling about the constitutionality of juveniles being sentenced to life in prison, Lambrix's lawyers wrote. Last year, the Florida justices gave inmates who had been sentenced to life as juveniles two years to seek new sentences from trial courts.

Source: tbo.com, January 23, 2016

End, don't mend, Florida's death penalty

|

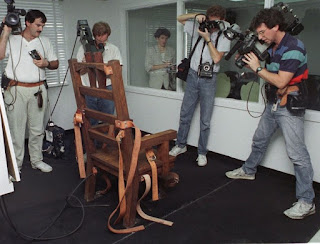

| Florida's electric chair |

It is time to abolish the death penalty in Florida as an outdated form of punishment that is arbitrarily applied, costs too much time and money, and fails to deter criminals or provide timely comfort to victims' families.

The Florida Supreme Court will hear arguments next month on whether a recent U.S. Supreme Court opinion that overturned the state's sentencing process in death penalty cases should apply to scores of death row inmates who already have been sentenced. Attorney General Pam Bondi and state lawmakers vow to overhaul the sentencing system, but the death penalty is not worth the trouble. It is time to abolish the death penalty in Florida as an outdated form of punishment that is arbitrarily applied, costs too much time and money, and fails to deter criminals or give timely comfort to victims' families.

The U.S. Supreme Court struck down Florida's death sentencing laws this month, ruling in an 8-1 decision that Florida's system was unconstitutional because it vests final authority in death cases in judges instead of juries. The Florida Supreme Court will visit a narrow issue in oral arguments on Feb. 2: whether the decision in Hurst vs. Florida should be applied retroactively to the 390 inmates on death row. But there are much larger problems with the death penalty that cannot be resolved.

Here are 6 reasons Florida should end rather than fix the death penalty:

It's arbitrary. There are 31 states that allow the death penalty, but it is largely a punishment imposed by Southern states. Texas, Missouri and Georgia accounted for 86 % of all executions last year. In the past several years, Florida has ranked in the top 3 states for executions.

While some states have stopped executions entirely over the past decade, with some abolishing them outright, the arbitrary nature of who is sentenced to death has grown more obvious as it is meted out in a shrinking sliver of the country. In 2012, 59 counties - fewer than 2 % of all those nationwide - accounted for all death sentences imposed in the United States. That speaks to the political pressure of individual cases that locally elected prosecutors and judges face. It's a trend that promises to become more pronounced as the number of death sentences continues to drop to the lowest levels since the U.S. Supreme Court reinstated executions in 1976. Florida is on the wrong side of this trend.

It's expensive. The financial cost of bringing a capital case to trial is another example of how similar crimes can be treated differently because of outside factors. Studies show that death cases cost four times or more as much as cases where the death sentence is not an option. Prosecutors and defense attorneys are forced to hire experts, travel and spend huge amounts of time preparing for trial, consuming resources that state attorneys, public defenders, private lawyers and the police could better spend on other law enforcement efforts.

Death row inmates are also more expensive to house, and the appeals process can drag on for years, sapping even more public money and resources. The net effect is that states and local authorities must pick and choose, and in an era of tight government budgets, some defendants will benefit and some will lose merely on the basis of which jurisdictions can afford to prosecute a capital case.

Its value as a deterrent is questionable. Those on both sides of the death penalty deterrence argument claim that research validates their position. But a landmark study in 2012 by the National Research Council of the National Academies, whose members are chartered to advise the federal government on the sciences, technology and public health, concluded that research over the past 3 decades "is not informative about whether capital punishment decreases, increases or has no effect on homicide rates." The academies found that the research to date was so fundamentally flawed that neither side could argue the deterrent effect.

The finding reinforces the argument by opponents that the death penalty is too compromised by delays, procedural error and bias to deter the criminal population.

It takes too long. The length of the average delay nationally between sentencing and death has increased significantly over time, from 11 years in 2004 to 17 years today. Of the 28 people executed nationwide in 2015, 3 waited nearly 30 years or longer. In Florida, the 20 inmates executed from 2012 to last year spent, on average, nearly 25 years on death row.

It does not provide certain closure. The death penalty is also not a salve to the victims' families, who are forced the revisit the loss of a loved one multiple times over years of waiting for a final resolution. Trials in death cases involve 2 stages - a guilt phase and sentencing phase - meaning that victims must endure the heinous details of a murder over an extended period.

That is just the beginning. The appellate process adds years if not decades to a capital case, and victims looking for comfort and certainty are left in a painful limbo for an indeterminate time. The constant reprise of the tragedy makes it harder for them to recover, and it forces families to continually focus on the worst times of their lives.

It is not error-proof. Scores of people nationwide have been freed from death row after being wrongly convicted, revealing a troubled system that new advances in forensic science will continue to expose as vulnerable to error.

There is no shortage of factors that can contribute to wrongfully sending a person to death row, from mistaken witnesses and forced confessions to perjured testimony, incompetent defense attorneys and false or planted forensic evidence. Nearly 160 people sentenced to death have been exonerated since 1973 - a figure that equals one of every 10 people executed nationwide since 1976.

Florida, which leads the nation in exonerations, at 26, should be working to improve its criminal justice system, not looking for ways to speed up executions or to patch its procedural flaws.

The death penalty is a relic of an earlier era that is increasingly avoided, marginalized geographically and takes decades to carry out. Rather than overhauling the sentencing system to comply with the U.S. Supreme Court, Florida should abolish the death penalty.

Source: Tampa Bay Times, Editorial, January 23, 2016