Scott Peterson is guilty of adultery but not murder, his sister-in-law said in the family's 1st comprehensive video interview with The Modesto Bee since his pregnant wife, Laci Peterson, went missing nearly 16 years ago.

"We don't have justice yet; we're not there," Janey Peterson said. "We can't be content thinking we know what happened to Laci and Conner; we don't."

This week, Scott Peterson's lawyers are filing a final court document aimed at reversing the death-penalty verdict their client received in December 2004.

It's the last in a standard series of 6 written pleadings before the California Supreme Court hears oral arguments and decides whether the 1-time Modesto man will be executed for murdering his pregnant wife and their unborn son at Christmastime 2002.

The Supreme Court has overturned 10 % of the nearly 200 capital punishment verdicts it has reviewed since 2009. So far this year, the court has reversed 1 of 16 death-penalty decisions.

Janey Peterson sat down with The Bee for a lengthy conversation 2 weeks ago, with his appeals milestone fast approaching.

Laci's mother, Sharon Rocha, has accommodated similar sit-down requests with The Bee, notably in January 2006 and in December 2007. She and others of Laci's loved ones over the years steadfastly have maintained their belief that justice was served at Scott Peterson's trial. In April 2016, for example, Rocha summed up her thoughts: "Scott Peterson is guilty."

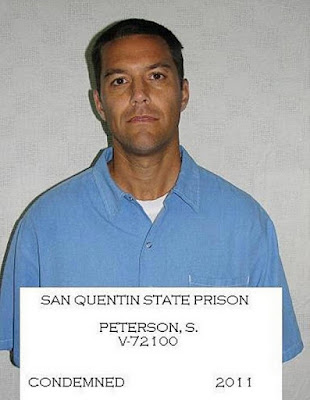

Scott, now 45, always has said he's innocent, and his family believes him. Janey Peterson's main message reflects the objective of 957 pages in his appeal documents, saying he is owed a new trial.

What about the 12 jurors who absorbed 6 months of trial and testimony from 184 witnesses, and determined that he's guilty? Could all 12 jurors be wrong?

"I think the verdict they made," she said, "was an emotional verdict based on adultery evidence. The pile of evidence that showed Scott was an adulterer was used to convict him of murder."

Agreed-upon interview topics included major points raised in the appeals, most having to do with the 2004 trial itself - whether the judge, jurors and attorneys went astray enough to require a do-over. Some interview subjects were off limits, like Laci's family, and Amber Frey, Scott's lover when Laci went missing.

Janey Peterson talked a bit about her family, and also about her brother-in-law, providing a peek at his life in San Quentin State Prison.

The television in Scott Peterson's cell, for example, gets only major network channels and public TV, so he's missed most of the cable news shows about his case - 8 in 2017 alone - that have popped up in the past couple of years while the culmination of his appeals draws near.

2 1/2-hour "contact visits," in a cell with him, can be paid on Thursday, Saturday and Sunday; they can stretch it to 5 hours because most family members live in the San Diego area and must travel more than 250 miles. He gets such visits about every other week. Because he was convicted of murdering a minor - Conner, who Laci was carrying in pregnancy - Scott's nieces and nephews must be at least 18 to visit.

Near the end of the blockbuster 2004 trial, defense attorney Mark Geragos glumly shared with jurors a vision of a prison guard someday knocking on Peterson's cell to say his mother had died, followed later by more knocking and news that his father had died. Jackie Peterson, Scott's frail mother who used an oxygen tank in the courtroom audience, indeed died in 2013, but notifying Scott didn't happen that way; Janey was scheduled to pay him a visit that day, and broke the news in person.

"It was a hard day," Janey said. "Visiting in the cell, with people around you 360 (degrees), it was not a private place at all. I didn't let myself get emotional on the way up. When I told him, the next couple of hours we really restrained ourselves. For him, it was something we didn't want to deal with in a public way. That was very hard to do."

Asked how his father, Lee Peterson, is holding up, Janey paused 35 seconds, gathering herself before answering. On the witness stand, Lee had described Scott as his best friend.

"I don't know if you can understand how Lee is holding up unless you understand the (gravity) of this injustice. As much as us kids feel it, I don't know if I can put myself in Lee's shoes as a parent, or in Jackie's shoes. Or in Sharon's shoes," she said. "I just can't even comprehend it."

Janey spoke to The Bee in a reception area of the crate-building shop Lee established in 1975 when Scott was 3, in Poway, near San Diego. It's a family business, employing several kin including Janey and her husband, Joe, Scott's brother. Scott spent untold hours here as a youth and young man, working in the manufacturing area, moving among offices and delivering custom-built wood crates to clients needing protection for airplane parts, machinery and the like.

A small office lacking air conditioning serves as a legal strategy room, containing reams of information on the case. Some walls are covered with FBI-type timelines pinpointing Scott's known actions on the day Laci went missing, juxtaposed with what the family believes Laci, 27, was doing, with a neighborhood map reflecting reported sightings of Laci walking the couple's dog. Boxes of notes line the walls. In a finished wooden cupboard - handcrafted long ago by a young Scott Peterson - are binders filled with 45,000 pages of evidence, plus others with transcripts of the 6-month trial.

"Over the years, everything we've learned either further exonerates Scott or takes us one step closer to finding out what happened to Laci and Conner," Janey said.

Like Laci, Janey is a Peterson by marriage. She spoke briefly of her sister-in-law.

"We watched (Scott and Laci) grow up when they were first dating, and watched that progression of life, them starting to plan a family - that's why they moved to Modesto (Laci's hometown), to start a family. To see them own a home, the love they put into ... that home, and preparing for Conner. You could see who she was in all those things."

On Christmas Eve 2002, Scott left home to fish in San Francisco Bay, hauling a recently purchased 14-foot aluminum boat. Authorities believe he also hauled Laci's body, weighted with homemade concrete anchors, dumping her in the water near where the remains of mother and son washed up nearly 4 months later.

His family believes, and Geragos argued to jurors, that unknown abductors put Laci's body exactly where the whole world knew Scott had been fishing.

Jurors didn't buy it. Whether the Supreme Court does isn't really the question; it's whether Supreme Court justices find that enough went wrong in the trial to warrant a new one.

The original trial judge, Al Delucchi - who died of cancer in 2008 - once mused that both sides would have much to argue over in the appeals process. "With all the issues that have been raised," Delucchi said in October 2004, "if there is a conviction in this case, it will be an appellate lawyer's petri dish."

Now that the appeals are here, what's growing in that petri dish? Janey Peterson addressed a few points she hopes will resonate with the Supreme Court.

Neighborhood sightings

Several people reported seeing a pregnant woman walking a dog in the couple's neighborhood or nearby East La Loma Park that morning. If true, Scott must be innocent, his camp says, because it all happened after he left the home on Covena Avenue about 10 a.m. on Dec. 24, 2002.

Geragos did not call those people to the witness stand, presumably because none fit in a timeline established when neighbor Karen Servas found the Petersons' golden retriever, McKenzie, in the street with a walking leash attached to its collar, and put the dog inside the Petersons' gate at 10:18 a.m. Scott later told police he found the dog in the yard, leash still attached, when he returned from fishing.

Was it a mistake not to explore these witnesses' testimony at trial?

"You've got to say 'yes' to that; look where we're at," with Scott on death row, Janey said. "The jurors need to hear from those witnesses. And the jurors need to decide the credibility of the sum total of all witnesses in the case."

Burglary

A home directly across the street was burglarized, also after Scott left. Prosecutors said the crime was unrelated to Laci's disappearance, but Scott's attorneys realized too late that they should have done more verifying.

One of the burglars, imprisoned for that crime, later told people that he verbally threatened Laci Peterson when she confronted him that morning.

And a mailman told police that the Petersons' dog did not bark and that the gate was open when he delivered mail after Servas encountered the dog, suggesting Laci and McKenzie had gone on a walk after all.

"The one scenario that all these eyewitnesses fit is the 'Scott is innocent' scenario. That's the only answer," Janey said. "They all have to be wrong: the mailman has to be wrong, the (burglar confrontation) tip has to be wrong, the inmates on the phone have to be wrong, all the people who say they saw Laci walking her dog have to be wrong" for prosecutors to be right, she said.

Dogs

Attorneys on both sides had lengthy arguments over whether scent-dog tracking evidence should be admitted at trial. Delucchi disallowed almost all at the Peterson home and at Scott's warehouse in west Modesto, where he had hitched up the boat trailer. But the judge decided to allow testimony that a dog indicated, 4 days after Laci vanished, detecting her scent at the Berkeley Marina, where Scott had launched the boat.

Geragos must have been proud at having persuaded the judge to exclude most of the dog-tracking evidence. But jurors latched onto the marina alert, some later saying it was critical to the guilty verdict. Scott's appellate attorneys now argue that the marina alert also should have been tossed, because scent tracking is an imperfect science and dogs and handlers make mistakes.

"It was prejudicial against Scott," Janey said. "At the time, it was not real common for dog handlers to testify as to what the dog was thinking or doing. The science behind dog handling doesn't meet the threshold (for) a jury in a courtroom."

Boat

Before trial, Scott's defense team videotaped a re-enactment showing a man Scott's size trying to shove a dummy about the size of Laci's body out of a floating boat similar to Scott's, swamping the boat. Geragos wanted to show the video to jurors, but Delucchi said "no," reasoning that the boat was not exactly the same and prosecutors weren't present at taping to verify conditions, essentially preventing them from cross-examining the video.

But Delucchi let prosecutors re-enact a pregnant woman about Laci's size fitting in a large toolbox in the bed of Scott's pickup, which authorities think he might have used to transport the body, Janey noted. And the judge also allowed prosecution testimony about stability experiments on the same boat model performed in a freshwater swimming pool in Indiana 25 years before the trial.

Why didn't Geragos accept Delucchi's offer to let the defense team redo another re-enactment with the actual boat, with authorities watching?

"That would be a constitutional violation of Scott's rights," Janey said. "It's not a part of what a defense should have to do."

Jury selection

Choosing a jury before trial became a nearly 3-month ordeal. Both sides and Delucchi worked through nearly 1,000 questionnaires of prospective jurors, and questioned hundreds before agreeing on the final panel.

Scott's appellate lawyers now contend Delucchi erred when he excused 30 prospective jurors based solely on their written answers, where they professed opposition to the death penalty. Each should have been orally questioned to see whether they might set aside personal opinions to apply the law in some circumstances, the appeal says.

"That's an example of error," the kind that requires redoing the trial phase where jurors decided he should be executed, Janey said.

Is it really a big deal?

3 weeks ago, the California Supreme Court cited the same reason in reversing a death penalty verdict for Steve Woodruff, who killed a Riverside police detective in 2001. That judge had improperly excused one prospective juror, justices found.

Would Scott's family be satisfied with a retrial of just the penalty phase?

"No," Janey said. "Scott needs a new trial from the beginning. That's just 1 of the issues in appeal."

Richelle Nice

Another juror, Richelle Nice, did not reveal that her then-boyfriend's ex had threatened them when Nice had been pregnant, before the trial.

"That woman spent time in prison, or jail. That would have been something the defense should have had a right to know, and excuse her as a juror," Janey said.

In September, Nice told The Bee that the woman spent a week in jail for vandalizing the boyfriend's car and the door to their home, not for murdering two people. She didn't include the information on her pretrial questionnaire because it didn't seem remotely similar, Nice said.

Appeals process

Death row inmates pursue 2 appeals handled by 2 sets of attorneys.

One questions fairness in the trial, including a judge's alleged missteps. The other, called a habeas corpus petition, typically attacks the performance of a defense attorney, in this case Geragos, and can focus on new evidence, such as the revelations about Nice's past.

In both sets of appeals, the inmate begins by filing an opening brief. It's a misnomer; Peterson's 1st was 470 pages. The state attorney general's office responds with a written brief on behalf of prosecutors, followed by the inmate's final reply. That's 3 briefs for each appeal, or 6 in total.

The only written step left in Peterson's case is this week's final reply on the habeas track. All then will wait for the Supreme Court to schedule oral arguments, which could take 3 or 4 years, followed by more years of appeals on other levels, if warranted.

"The justice system doesn't always get it right," Janey said, referring to the initial trial, moved from Modesto to Redwood City because of prejudicial saturation here.

"We're still in the appellate part of the justice system," she continued. "So we have to still have hope and faith in our justice system, that they'll get it right."

Source: modbee.com, Garth Stapley, August 7, 2018

⚑ | Report an error, an omission, a typo; suggest a story or a new angle to an existing story; submit a piece, a comment; recommend a resource; contact the webmaster, contact us:

deathpenaltynews@gmail.com.

Opposed to Capital Punishment? Help us keep this blog up and running! DONATE!

"One is absolutely sickened, not by the crimes that the wicked have committed,

but by the punishments that the good have inflicted." -- Oscar Wilde