He's Watched 21 Men Die

Alan Johnson retired from the Columbus Dispatch last year. During his preceding tenure at the paper, in addition to a host of other topics, Johnson reported on Ohio's executions for 18 years. Of the 55 men put to death in the state since 1999, he witnessed 21 of them; he covered the majority of the rest from the grounds of Lucasville.

It's a role he had to fight for and one, quite frankly, he would rather not have had. But, as Johnson says, it's fundamental and essential for the media to bear witness to these deaths, and through them, the public.

Those experiences over almost two decades have left Johnson with a unique perspective on capital punishment — the mechanics of state-sanctioned homicide; the logistics of lethal injection and its recent issues of supply and secrecy; the range of emotions and reactions from families and victims; the problems when an execution goes awry; the almost dry, rote details one notices when it is, for lack of a better word, successful.

Johnson wrote about all that and more in a first-person piece for Columbus Monthly in August 2016. That article ends with the troubling death of Dennis McGuire on Jan. 16, 2014. A three-year moratorium on executions in Ohio would follow.

They have, of course, resumed, most recently with the aborted attempt to kill Alva Campbell after officials couldn't locate a suitable vein for the process. (His execution has been rescheduled two years from now; his lawyers have recently argued their client should be allowed death by firing squad instead of being subjected once again to a failed lethal injection.)

Up next is Raymond Tibbetts, whose date in the Death Chamber is next Tuesday, Feb. 13. (An original juror in that case recently

wrote a letter to John Kasich asking the governor to commute the sentence to life without parole for a variety of reasons, but we digress.)

Given all that has happened in the past three years, we asked Johnson to update his piece. He's done so, for this week's cover story, with the same keen eye that produced the original. You can read the full tale in print this week. As for reading it online, that's a slightly different story. Part of the peculiar republishing agreement with Columbus Monthly for this story was a requirement that we not upload the full version online. That's too bad, but as Frank Jackson says, it is what it is.

You have three options here. First: You can pick up a physical copy of this week's Scene and enjoy it there. Second: You can check our our e-edition at this

link and read the full thing in one place in PDF form. Third: You can head over to Columbus Monthly's site and

read the original piece, stopping at the section headed "The Last Execution," and then come back here for the updated ended, which you can find below. Not ideal, we know, but the story was worth sharing with a larger audience and it's simply the conditions laid out by the original publisher.

***

The Last Execution, For Awhile

The most troubling execution I witnessed in 18 years was when a gasping, struggling Dennis McGuire was put to death on Jan. 16, 2014. McGuire did not go easily.

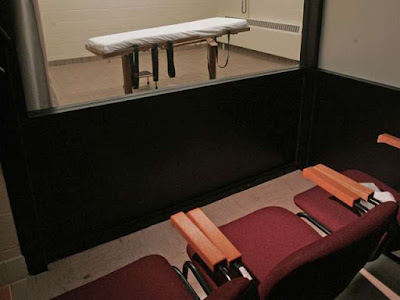

Things appeared to be going as planned until about five minutes after the chemical cocktail began flowing into his veins. The state was using a two-drug combination that had never previously been tried in the U.S. Suddenly, McGuire began to gasp, cough and choke. A minute later, he gasped so deeply that his stomach heaved up and down. It continued for nearly 15 minutes. McGuire clenched his fists repeatedly and several times appeared to try to rise up off the table, only to be prevented by the restraints on his chest, arms and legs. His grown son and daughter looked on in horror, sobbing uncontrollably. The family members of Joy Stewart, the pregnant, 22-year-old victim, watched in stunned silence.

“Is this what’s supposed to happen?” one whispered.

My own anxiety grew by the minute, as McGuire tried in vain to stay alive. I found myself wondering if it was too late for prison officials to call it off, to end the death drama playing out on the other side of the glass. There was no way to unring the bell.

“Please die. Just die,” I remember thinking, thoughts that still haunt me.

At 10:52 a.m., about 23 minutes after the deadly chemicals began flowing, the curtain was pulled. Unseen, a physician listened for a heartbeat and found none.

In the weeks and months that followed, controversy swirled about what had happened and why. The state said that an execution took place, as planned. Capital punishment opponents called it torture.

The state quickly abandoned the two-drug combination, but that triggered a search for new killing drugs. They were difficult to obtain because of the reluctance of drug manufacturers to sell drugs for use in executions. The General Assembly scrambled to pass a law allowing the state to make anonymous purchases from small “compounding pharmacies” that mix drugs to customer specifications. No Ohio pharmacies were interested in the state’s business.

Gov. John Kasich was forced to push back all scheduled executions.

An Untested Combination

The state, without disclosing the source, was eventually able to acquire a supply of three drugs with the following amounts to be used for each execution: 500 milligrams of midazolam hydrochloride, a strong sedative; 1,000 milligrams of rocuronium bromide, a muscle relaxer; and 240 milligrams of potassium chloride, which stops the heart.

The new, previously untried combination was successfully used on Ronald Phillips, 43, of Akron, on July 26, 2017. It was Ohio’s first execution in three and a half years. Phillips received the death sentence for raping, beating and murdering three-year-old Sheila Marie Evans, the daughter of his girlfriend at the time, on Jan. 18, 1993.

The day before his execution, Phillips’ “last meal” request included a bottle of grape juice and a piece of unleavened bread for a prison-cell communion, in addition to a bell pepper and mushroom pizza, strawberry cheesecake and two-liter bottle of Pepsi.

In stark contrast to McGuire’s troubled death, Phillips died quickly and quietly at the prison near Lucasville. The process took just 22 minutes, including 12 minutes after a chemical combination began flowing into his veins. By the official time of death, 10:43 a.m., Phillips had lain motionless and not apparently breathing for several minutes.

Phillips gave a final statement choked with emotion, apologizing to the Evans family for his “evil actions” and thanking his family for their “support and faithfulness.” Phillips closed his eyes and a few minutes later appeared to be sleeping. His stomach heaved slightly and his mouth fell open, but there were no dramatic reactions. A single tear fell from his left eye.

The reaction from witnesses afterwards differed sharply.

Donna Hudson, the slain girl’s aunt, said, “It was too easy. I don’t know if God forgave him, but I don’t think I can.”

William Phillips, the condemned man’s brother, watched his sibling die, but did not speak to media after it was over. However, Allen Bohnert, a federal public defender who represented Phillips, said an extremely high dose of a drug midazolam acted like a “chemical curtain” to prevent Phillips from showing pain he was feeling. “Ohio once again experimented with an undisputedly unconstitutional drug,” Bohnert said.

A Botched Attempt and a Retirement

Phillips’ execution was the last I would witness or cover prior to my retirement from the Columbus Dispatch on Sept. 22, 2017. At that point, I had witnessed 21 executions and written about the majority of the 34 others to that point during a 33-year career.

While I had had enough of the “machinery of death,” as U.S. Supreme Court Justice Harry S. Blackmun called it in 1994, the state of Ohio continued forward, lethally injecting Gary Otte of Parma on Sept. 13, 2017. Otte, 45, robbed and murdered Robert Wasikowski, 61, and Sharon Kostura, 45, at an apartment in Parma in 1992.

The Associated Press reported that Otte's stomach “rose and fell repeatedly” for several minutes after the first drug, midazolam, was administered. One of Otte’s public defender attorneys hurriedly called a federal judge in Dayton, seeking to stop the execution, but the request was refused.

Ohio’s capital punishment process stumbled again with the aborted execution of Alva Campbell of Columbus on Nov. 15, 2017. Campbell’s lethal injection was called off after members of the prison execution team were not able to find intravenous access to administer the lethal drugs.

The Columbus Dispatch reported the execution team attempted for more than a half hour to find suitable veins on Campbell’s arms and one leg, before Gary Mohr, director of the Ohio Department of Rehabilitation and Correction, who was on the scene, halted the process. Campbell, who was sentenced to die for killing Charles Dials, 18, during a carjacking in Columbus on April 2, 1997, had a host of health problems. He was allowed to have a wedge-shaped pillow behind his back on the injection gurney for the execution to assist his breathing.

Campbell’s attorneys asked the state to allow him to be executed by a firing squad, but a federal judge turned down the request since state law allows only one method, lethal injection. The General Assembly would have to approve adding a new means of execution.

Kasich set a new death date for Campbell of June 5, 2019.

Ohio has four executions scheduled this year (out of 27 slated through 2022). First up on Feb. 13 is Raymond Tibbetts, 60, a Cincinnati man who killed his wife, Judith Crawford, and Fred Hicks, for whom Crawford was caregiver, on Nov. 5, 1997. Unlike Campbell, Tibbetts has no serious health problems, although his attorneys argue he should receive clemency because of an abusive childhood and an opioid dependency acquired as an adult. The Ohio Parole Board disagreed, recommending 11-1 against clemency, but Kasich has the final word.

My direct involvement with capital punishment in Ohio has come to an end. I won’t miss Lucasville, but I continue to think about the price it extracts on the families of victims and inmates, on prison employees, and on the public at large.

Being a witness to death is an important job, but I don’t mind that someone else will be watching from here on out.

Source: clevescene.com, Vince Grzegorek, February 7, 2018

⚑ | Report an error, an omission, a typo; suggest a story or a new angle to an existing story; submit a piece, a comment; recommend a resource; contact the webmaster, contact us:

deathpenaltynews@gmail.com.

Opposed to Capital Punishment? Help us keep this blog up and running! DONATE!

"One is absolutely sickened, not by the crimes that the wicked have committed,

but by the punishments that the good have inflicted." -- Oscar Wilde